Visionary or Disaster; a perspective on William Sargant

We don’t hear very much about William Sargant now, but in his day, he was the most eminent figure in British psychiatry, a large man with a leonine profile and convictions as strong as his character; somebody you obeyed and never argued with. David Owen, one time British foreign secretary, worked under Sargant at St Thomas’ in the 1960s and recalled him as “a dominating personality with the therapeutic courage of a lion” and as “the sort of person of whom legends are made”. But others, who preferred to remain anonymous, described him as “autocratic, a danger and a disaster” He was a man who could excite strong opinions.

Although he was part of the listening profession, Sargant wasn’t a great listener. Describing himself as “a physician in psychological medicine”, he abhorred psychotherapy and dedicated his life to leading the biological revolution in psychiatry, promoting such treatments as psychosurgery, deep sleep treatment, electroconvulsive therapy, insulin shock therapy and the development of mind altering drugs. He had the courage of his convictions, but his reliance on dogma rather than evidence have made him a controversial figure. His book, Battle for the mind, a physiology of conversion and brainwashing, written with the help of Robert Graves, emphasises the apparent need for evangelists and politicians who would change people’s minds to excite them first.

William Walters Sargant was born in 1907 into a ‘larger than life’ Methodist family in North London. Five of his uncles were Methodist preachers, one brother was a bishop; another, Thomas Sargant, a human rights campaigner.

He got a place at St John’s College, Cambridge and became President of The Cambridge University Medical Society. He did his clinical training at St Mary’s, where he excelled in the Hospitals Rugby Competition. Too impulsive and sure of himself to be a great academic, his one foray into medical research, a paper on the use of large amounts of iron to treat pernicious anaemia was criticised and this may have led to his mental and physical breakdown and his subsequent shift to psychiatry, where the absence of validated treatments gave him free rein to develop his convictions.

It was at the Maudsley under Edward Mapother that Sargant became convinced that ‘the future of psychiatric treatment lay in the discovery of simple physiological treatments which could be as widely applied as in general medicine‘. During the war, Sargant worked at the Sutton Emergency Medical Service but was frustrated when London County Council medical advisors tried to curb his experimentation with new treatments but, as he said “we generally got our own way in the end”.

While at Sutton, Sargant treated veterans with battle trauma by abreaction, deliberately getting them to relive their experience on the premise that it would eventually wear away. He described a man who was shot at by German pilots as he swam out to the boats at Dunkirk, experienced all over again the terror of drowning but then walked away from the session without a care in the world. Sargant never really validated or controlled his studies or even analysed the results of his treatments. He was no scientist; he just did what he considered right.

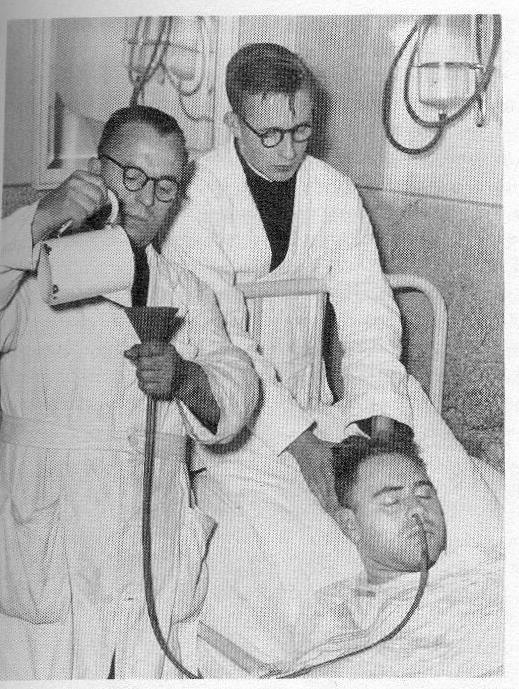

In 1948 he was appointed director of the department of psychological medicine at St Thomas’s Hospital, London, and remained there until the 1980s. There he developed his procedures for ‘brainwashing’ . He created a 22 bed sleep ward on the top floor of the adjacent Royal Waterloo Hospital,, in which he would keep his traumatised patients in a continuous state of heavy sedation for periods of up to three months and subject them to insulin coma therapy and frequent electroconvulsive treatment. This brainwashing, he claimed, re-patterned the brain, wiping it clean of the traumatic experience so that when they woke up they couldn’t remember what had happened .

Sargant also advocated increasing the frequency of ECT sessions for those he describes as “resistant, obsessional patients” in order to produce “therapeutic confusion” and so remove their power of refusal. “All sorts of treatment can be given while the patient is kept sleeping, including a variety of drugs and ECT [which] together generally induce considerable memory loss for the period under narcosis. We may be seeing here a new exciting beginning in psychiatry and the possibility of a treatment era such as followed the introduction of anaesthesia in surgery”.

No informed consent was requested for what was an experimental procedure. No systematic study ever validated Sargant’s cerebral lavage, but there are patients still alive who claim never to have recovered their pre-traumatic memory and become profoundly incapacitated as a result. Sargant, himself, ascribed such failures to the patient’s lack of a “good previous personality” and discharged them to the wards of long stay mental hospitals. These patients have never been compensated. All patient records at St Thomas’s and the related health authorities relating to Sargant’s activities were destroyed.

But there was worse. When Harry Bailey, an Australian psychiatrist enthusiastically adopted Sargant’s methods with enthusiasm, 26 of his patients died. Sargant also admitted some fatalities. The fact that more had not succumbed was almost certainly due to the quality of care by the St Thomas’s ‘Nightingale’ nurses, who monitored the patients sleep every 15 minutes and woke them up every six hours for feeding and toileting.

Sargant’s ward was closed soon after his death in the 1980s; his books removed from the libraries, his influence suppressed, his opinions castigated.

One of my teachers, a surgeon, used to tell us that there were three types of doctor; the good, the bad and the downright dangerous. Sargant was the latter. Evangelism and conviction are dangerous qualities in medicine and Sargant has been roundly condemned as ‘someone of extreme views who was cruel and irresponsible and refused to listen to advice’; some suggested that he was motivated by repressed anger rather than a desire to help people. In medicine, tyranny is dressed in a white coat.

But Sargant was a man of his time. Revolutions would not occur without the extremist, the outspoken, the dogmatic and the domineering. So those who would praise modern developments in the pharmacological treatments of schizophrenia, dementia and depression, have a debt of gratitude to Sargant the prophet, who had to be condemned for his extremism.

For medicine is a profession that requires us to listen, make careful observations and assess any new definitive treatments by the most scrupulous scientific methods. Doctors have to be seen as caring and careful. I once knew a doctor who had the unfortunate surname of Reckless; he should have changed it.

But, in Sargant’s defence (which is a bit like the defence of indefensible) the effects of new psychiatric treatments are not easy to assess. There are no measureable end points like inflammation, blood pressure, blood sugar levels. There’s just patient testimony. ‘Yes, I’m feeling much better, thank you.’ Good results may be more due to the care and attention of the doctors and nurses than any effect of the treatment. It all depends how you ask the question and what statistical methods are applied. Powerful advocates and suggestible patients can still produce ‘effective’ treatments. Perhaps that’s the nature of the mind; it’s confidence and faith that heals the traumatised psyche – and there are many routes to that. In a therapeutic wilderness, the most important thing is to be mindful to select treatments that do not have the potential to damage.

Take antidepressants (or don’t take them), the most commonly prescribed drugs in the western canon. Are they effective, or do they just dull the sensibilities, sanitise the anguish and despair, and keep people in depression by suppressing the motivation for change?

Even Sargant acknowledged, albeit in typical grandiose manner, how psychiatric treatments may strip away the personality and motivation.

“What would have happened if such treatments had been available for the last five hundred years?… John Wesley who had years of depressive torment before accepting the idea of salvation by faith rather than good works, might have avoided this, and simply gone back to help his father as curate of Epworth following treatment. Wilberforce, too, might have gone back to being a man about town, and avoided his long fight to abolish slavery and his addiction to laudanum. Loyola and St Francis might also have continued with their military careers. Perhaps, even earlier, Jesus Christ might simply have returned to his carpentry following the use of modern treatments.”

A recent systematic review could not establish any efficacy for the newer antidepressants, the latest generation of Sargant’s mind altering drugs, though they all have significant adverse effects. So why are billions still taking them? What does it say about society and those who run it?

Sargant, the maverick, the charismatic loner, the one who dared but was considered out of step and downright dangerous, was as described in his autobiography, ‘A Quiet Mind’, a heavy smoker, suffered with tuberculosis and struggled with depression for most of his life. It was his karma, (the collective guilt of a family of preachers?), and he lived up to it by putting his patients and his own reputation in considerable danger. Was this some death wish, some demon of self destruction? Winston Churchill, another depressive, comes to mind; so wonderful but so dangerous – relishing the excitement of risk, rushing up to the roof of 10 Downing Street during the blitz to watch the fireworks, but suffering agonies during peacetime inactivity. No wonder Clemmie found him difficult.

David Owen who admired Sargant’s courage and spirit, has recently written a slim volume on hubris, in which Sargant doesn’t even get a mention. Ah!

William Sargant was the subject of a Radio 4 documentary ‘The Mind Bender General’, first broadcast in 2009 and repeated last Wednesday.

A lot of this information is inaccurate, William Sargant can’t defend himself. I was treated by him successfully using medication which was regarded as a dangerous combinations by most of the medical profession

To say again how good a doctor William Sargant was.When he died I sene a letter to his widow saying how her husband had been a God send to me during my mental illness.She responded saying she had recived many simliar letters from his patients .Also when he went into private practise he had lots of patients who he treated of there own will ! He also said to me you can not live in a chemical world.I get absolutley fed up with people running him down especialy when he is no longer here to defend himself !!

Stewart Reeve

In this era in which human societies, certainly ours in the United States, seem like one vast sociological experiment (absent discernible elements of intention or purposeful study), the need to understand how people are influenced, how readily we submit to suggestion and the power of “groupthink” become powerfully relevant. William Sargant’s book “The Mind Possessed” is helpful not only for insights conveyed on nearly every page, but also for questioning processes evoked in a thoughtful reader’s mind. Few authors address subjects of such importance without attempting to grasp a reader’s intellect and direct it solely toward the author’s conclusions. I don’t find this true with William Sargant’s writing, which supports processes of questioning, rather than attempting to control them. So I question efforts to belittle or demonize a man who (shock!) surely made mistakes at times but who shared valuable insights in how we tick, how we become broken, and how we may become more whole again. James Opie Portland, Oregon, USA

Here is a book (in Georgian, with English digest), which describes a place in Canada, where Sargantian brainwashing is still alive and well and is used on some political “patients”.

http://targetingbrainwashers.blogspot.com/

Amazing. Thank you for the information

I was one of those Nightingale nurses who looked after Dr Sargent’s patients – I hated the whole way of treating people like this and agree with the fact that psychotherapy is growing in popularity and patients are given a chance to heal themselves of all their background pain also medication has become so much more sophisticated and slowly attitudes to mental illness are changing, thank goodness – after all we are all on a spectrum and WHAT is Normal?

The spiritual has always been an aid in healing and the vast growth of people using the 12 steps of AA, which after all, is an entirely spiritual programme for people who want to get better and are prepared to work hard at their addictive problems.

How interesting, Jandy. Yes, attitudes to mental health are changing, but too slowly. I agree, we are all on a spectrum and can shift along that spectrum according to what is happening. More attention needs to be paid to ‘healing’ rather than treatment. Thank you for your useful comments.