From Mount Wehni to Kentish Town

‘They say you will all die!’

Mulu’s cries add a chill to the low afternoon sun.

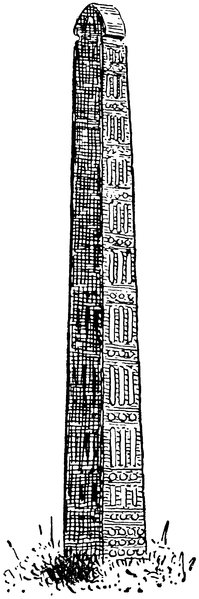

The villagers had been on the hillside opposite the ambo, the basaltic stele that we were attempting to scale, all day, laughing and shouting cries of encouragement. But now it was late, night was imminent and they had begun to panic. If we spent the night on the mountain, the spirits would surely kill us.

We had started well. There was a clear diagonal line up the western face that must have marked the site of the original steps. But this soon ended and we were forced to muscle our way up a greasy chimney to a precarious ledge, occupied by bellicose baboon, who, after much lip curling and smacking, turned, and with slow disdain, presented his rump and strolled back the way he had come.

It was too dangerous to reverse our route in the dark. We would have to bivouac on the narrow ledge. The problem was that we only had the fly sheet to shelter under if it rained and just two sleeping bags between the four of us. Mike and I wedged our legs into one and tied ourselves to the base of stunted tree, but in the middle of the night I awoke to find our ties had worked loose and the entrapped bottom halves of our conjoined bodies were suspended over a four hundred foot drop. I nudged Mike, who turned over, propelling us further out of our centre of gravity. It looked as if the villagers prophecies were about to be realised. But no. Gently I awoke him and moving very cautiously and hooking our arms around the tree without uprooting it, we managed to pull ourselves up. Although we strengthened our ties, we had no more sleep that night.

Mount Wehni was in the northern highlands of Ethiopia, not far from the ancient capital of Axum. It had not been climbed for four hundred years. Then it was a prison. The Emperor kept any challengers to his throne incarcerated in the huts on the top. The only way up and down the perilous pillar of rock was a wood and rock staircase, but that had collapsed. Cut off from supplies in their inaccessible eyrie, the prisoners and their guides perished.

In 1966, as a second year medical student with a yearning for adventure, I and a group of like-minded friends organised The Cambridge Medical Expedition to Ethiopia to carry out a survey on the prevalence of the debilitating parasitic illness, schistosomiasis, in areas of economic development. While we in Addis, we met a climber, Dave Prentice, who was on a personal mission to climb Mount Wehni and needed a few more foolhardy romantics to help him realise it.

We didn’t succeed. By midday on the second day, we were still a long way from the top. Reluctant to spend another sleepless night on the side of the mountain and concerned about our lack of water, we abseiled down.

The villagers welcomed us like spirits returned from the dead and prepared a banquet. There were large black glazed jugs of tej, a kind of honey mead, a bowl of we’t, a spicy lamb curry and plates piled high with injerra, a pancake made of the sourdough prepared from tef, a coase flour made from the seeds of a grass that grew in the highlands. We tore off pieces of injerra and used it to scoop up the we’t, sluicing it down with an infinite supply of tej. As the night wore on the villagers entertained us with songs and dances. We staggered back to our tent boisterous and happy at 3am. It was a feast, I shall never forget.

‘The Queen of Sheba’ is the one of a small number of Ethiopian restaurants in Britain. Situated on the corner of Fortess Road in Kentish Town, it is not posh, but it has character and the food in delicious. A strong aroma of incense greets you as you enter a dark candlelit interior. Plain wooden tables and chairs are placed around the small corner room. Amharic crucifixes, spears, shields, black earthenware jugs and lamps adorn the walls. A strange, haunting Ethiopian music is playing. This restaurant manages to recreate in Kentish Town, the atmosphere of a hut on the road to Lalibela. Time Out calls it a funky juxtaposition of ancient and modern.

‘The Queen of Sheba’ is is a family run business. Mother is the chef, father runs the accounts and the daughters, beautiful dusky temptresses with wild curly hair and high boots, serve at tables.

The menu features traditional Ethiopian classics, spicy meat or vegetarian we’ts, served on injerra, which has been cooked over steam and has the appearance and texture of a damp dish cloth but a delicious slightly acidic taste that complements the salty richness of the we’ts. There is also Kitfo, the Ethiopian equivalent of steak tartare, a delicious beetroot salad, spicy spinach and cottage cheese, and Kantegna, injerra toasted in butter and hot spices.

Ethiopian meals are rich in ceremony. The main course, which is often shared by 2 to 4 guests, is served on a large metal tray covered with a mesob, a conical rush cover, which is removed with a flourish to reveal a large flat disc of injerra covered in a variety of meat and vegetarian we’ts. More rolls of injerra are stacked up on the side. You eat with your hands, just as we did 40 years ago at the feast at Wehni. It is a pity they do not serve tej in Kentish Town, but the strong Ethiopian lager, Castle, has a good back of the mouth bitterness that works well with the acidic injerra.

There is no dessert, but it is essential to experience Ethiopian coffee.

Coffee is highly prized in Ethiopia. It was, according to legend, discovered in the highlands (see my blog, Frisky goats and dirty cats; the serendipity of coffee, 8th August, 2008). It is served with elaborate ritual. First the waitress arrives with freshly roasted coffee beans smoking on a metal spatula and presents it to each of us to smell. These are then taken away to be ground with cardamom seeds and a small piece of cinnamon bark and put in a glazed black coffee pot. Boiling water is added and the pot is placed on a rush ring on a metal tray together with two small cups without handles, a bowl of sugar and a small clay pedestal surmounted by a tablet of glowing charcoal upon which is smoking three small pieces of frankincense.

I sip my spicy coffee, waft the incense into my nose, close my eyes, hear again the haunting melody of the flute, the rhythm of the tabor, the excited chuckle of conversation and I am transported from north London to a balabat’s tukul on a ridge in the remote highlands of Ethiopia, where I celebrate with friends our miraculous deliverance from the spirits of Mount Wehni.