In search of meaning

‘To live is to suffer, to survive is to find meaning in the suffering. If there is any purpose in life at all, there must be a purpose in suffering and in dying. But no man can tell another what this purpose is. Each must find out for himself, and must accept the answer that his solution prescribes. If he succeeds, he will continue to grow despite all the indignities.’

So writes one time Harvard Professor of Psychology, Gordon Allport in his preface to Viktor Frankl’s abiding monument, ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’. He claims it as the central theme of existentialism. We might, however question whether it is always necessary to suffer in order to grow. There is something Calvinist in that notion. But what Frankl shows us through his narrative is how it is possible to withstand the most dreadful pain, torture and privation by finding and retaining an essential meaning in life.

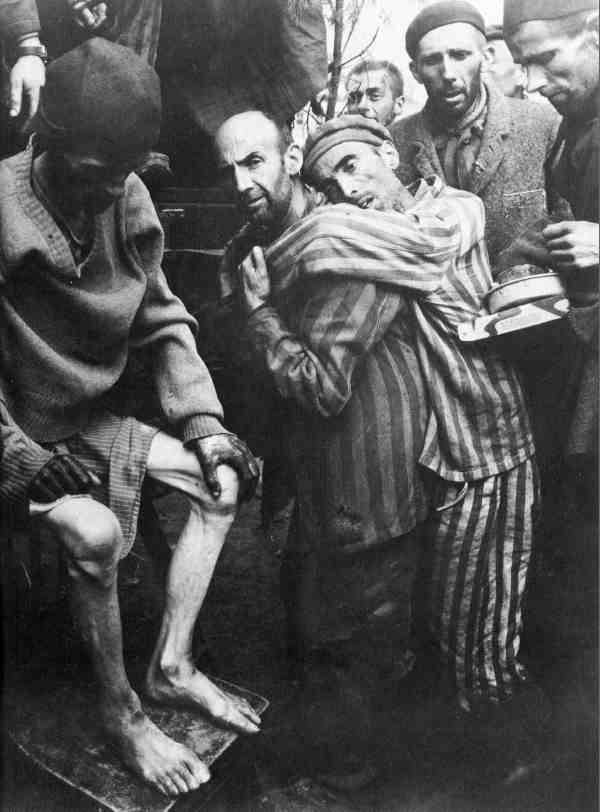

Viktor Frankl was a jewish psychiatrist, living in Vienna in 1939. He could have escaped to America; he had a visa, but he could not bring himself to abandon his parents to their fate. He was arrested by the Nazis and taken to Auschwitz, but he survived. He wasn’t a Capo, a privileged collaborator; he found the meaning in his suffering to survive.

‘Man’s Search for Meaning’ focuses on everyday indignities and privations, the cruelty, the lack of food, sleep and adequate clothing, the lice, dysentery, work, and endurance.

After the initial shock of becoming a number instead of a human being, a prisoner enters into phase of apathy and indifference. He tries not to be noticed, merges in with the crowd, gives an impression of smartness and fitness for work; does anything that would stop him being singled out and sent to the gas chambers. Many gave up, refused to work and accepted their fate, but those who survived discovered and nurtured an essential purpose in life that was worth clinging on to.

Frankl describes how the memory and love for his wife kept him alive. In the midst of the most dreadful degradation, he focussed on thoughts that uplifted the soul; an image of mountains, the coming of spring, music, snatches of poetry, the book he wanted to write.

There is nobility in suffering, Frankl claims, opportunities to find a moral compass and retain human dignity. Suffering can bring out the best in a person if he sees meaning in it.

Fyodor Dostoevsky said that the only thing he dreaded was not to be worthy of his sufferings. Those who let their inner hold on their own dignity and meaning, eventually fell victim to the camp’s degrading influence. They gave way to introspection and retrospection, lost purpose and hope, and just lay on their bed of stinking straw and were taken away to die.

Frankl described a strange timelessness in the camp. Hours or days of degradation and pain, passed slowly, but months and years passed quickly, punctuated by suffering. Survivors saw it as a provisional existence, something to be endured for as long as it took; they retained the hope they would be free.

Prisoners were supported by the companionship of mutual privation. They tried to help each other. They kept each other warm at night, they remove the lice from their hair, they shared their food, they told grim jokes. They were a kind of community; they trusted each other. Religion was a potent bonding force; prisoners often gained solace by praying together every night.

Unfortunately, their suffering did not always end when the guards left and the camp gates were opened . Release was all too often associated with bitterness and disillusion. Life had moved on. Their family had died. There was no work and they had lost the companionship of shared suffering. Others could not understand

For Frankl, his experience in Auschwitz became the mainspring of his life. From it he developed a philosophy of hope and a psychotherapy for those in despair, based on the discovery of the meaning of their suffering. It was Niezsche who said, ‘He who has a why (a purpose) to live can bear almost any how.’ Frankl explains that the ‘why’ of existence is was not so much what we expect from life, more what life expected from us in terms of work and family. Life ultimately means taking responsibility. Sometimes action is needed, sometimes contemplation, sometimes it’s just necessary to accept fate. When a man realises that suffering is his destiny, he will accept it as a challenge. Such thoughts can keep a prisoner from despair. Again, Nietzsche, ‘That which does not kill me, makes me stronger.’

Few of us in the west have ever been tested in the way Frankl was. But meaning can be threatened in other ways, such as the death of a spouse, the devastation of divorce, the collapse of love, the loss of purpose in retirement or unemployment, the estrangement from one’s children, the disillusion with a cause or faith. When people lose meaning and purpose, then they succumb to an inner emptiness, an existential vacuum, the boredom and loneliness, which lies at the base of much of the unhappiness of modern life.

Empty people try to fill their lives with thrills and diversions; the sexual libido becomes rampant in existential vacuum, so does the pursuit of power, the addiction to shopping, alcohol, drugs, the accumulation of money. It is pure escapism into immediate gratification, a frantic search for meaning in sensation. ‘We had such a wicked time, I got smashed, the sex was fantastic!’

Such diversions rarely lead to meaning. Quite the reverse; often the will, the hope, the purpose and the self respect dies a little more. Frankl states that people can transcend the thrill-seeking self and discover a meaning in their lives by creating a work or a deed, by experiencing something or encountering someone (such as falling in love), and most of all, by the attitude we take towards unavoidable suffering.

He claims that we can be ennobled by taking on the suffering another would have to bear, like giving up a relationship that would devastate them, an ambition that would cause them pain. This might give suffering a meaning, but it is avoidable. And is martyrdom and self sacrifice ever a valid route to redemption and happiness? Only if the sacrifice has a deeper meaning to the integrity of the ‘soul’, outside of the act itself.

Survival of identity and meaning (what I tend to regard as the soul) is more important than mere corporeal integrity. The anorexic starves their body so that their basic identity and meaning can thrive. And for many other sick people, illness endures the meaning of what has happened, until a person can bear to bring it to mind. If the meaning and purpose are devastated by life’s vicissitudes, then the body will easily become vulnerable to disease. Mind, body and soul (meaning) are a continuum, which contains health and happiness.

‘Man’s search for meaning’ was first published in 1946 in German under the title of ‘Ein psycholog erlebt das konzentrationslager’. Frankl developed the existential concept of logotherapy from his experience. Unlike psychoanalysis, logotherapy does not dwell on the past, but focuses on the development of a meaning in a person’s suffering that can break the cycle of loneliness and unhappiness.