Intimations of Hope

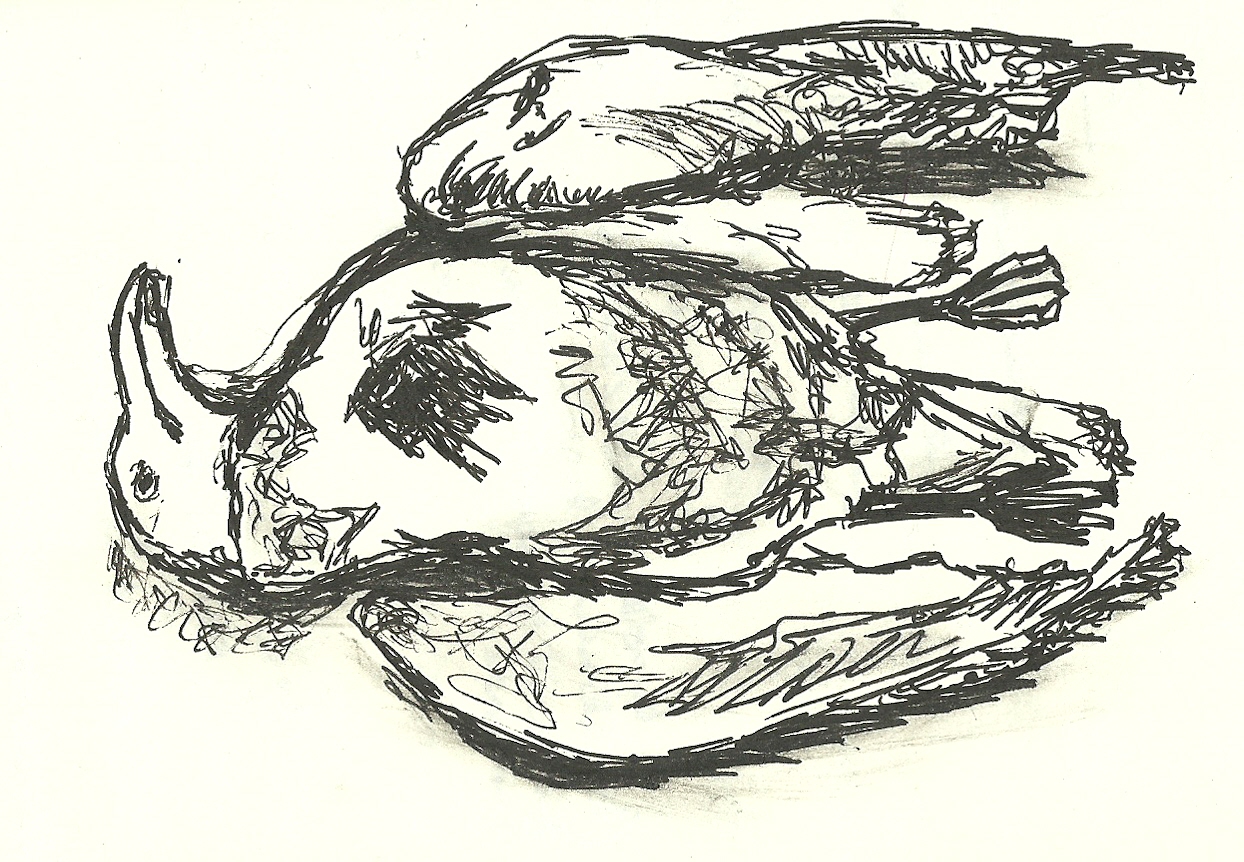

The idealistic Konstantin, humiliated by his famous mother, the actress Irina Arkidina, his play publicly dismissed as ridiculous, tries to shoot himself but instead shoots a seagull and presents the corpse to Nina, the daughter of a neighbouring landowner, whom he adores. Nina is disturbed and disgusted, but shows it to the sinister Trigorin, a famous writer and house guest, who notes down the metaphor for future use. Nina is in thrall to Trigorin. She sees in him an opportunity to escape the cage of the family estate and take flight as an actress. She follows Trigorin to Moscow, becomes pregnant and is rejected by the writer who is being kept by Irina. The baby dies, her family lock their gates against her, and she is transformed into the kind of tragic heroine that the painter, George Frederick Watts depicted in his allegorical studies of hope and poverty. She becomes the seagull.

Watts had taken as his child bride the teenage actress, Ellen Terry, in order to protect her from the same fate, or so the story goes. The marriage failed. It was supposedly never consummated. According to the amusing fiction by Lynne Truss, Watts just wasn’t interested in her that way. Released from Watts’ protection, Ellen soared upwards to become the most famous actress of her generation.

The Seagull possesses the usual Chekhovian themes; the country house, a self indulgent Russian bourgeoisie, decadent, bored and in decline, the threatening clouds of the oncoming revolution And the actors have the same familiar roles, the ageing actress and matriarch playing to the balcony while the theatre crumbles around her, the elderly and ailing uncle, the owner of the estate, representing old Russia about to vanish forever, the frustrated and bullish farm manager, fed up with the old ways and wanting progress, the desperate young author, the naive and fragile girl, and the doctor, perhaps Chekhov himself, a reflective observer, not entirely engaging with it all. Soon all will be scattered. Seen from this perspective, the seagull presents a broader perspective on the oncoming crisis, a fragile but beautiful way of life soon to be chopped down like The Cherry Orchard. Of course, the characters seem hysterical and self centred, they are all in love with love as a form of escape, the end of their world is coming; what else can they do? It wouldn’t be theatre if they all behaved sensibly and worked together.

The Seagull is currently playing at the Arcola Theatre in Stoke Newington; not an area I know well but accessible via the London Overground. The theatre is a converted warehouse. The set and seating are rough and ready but the cast and direction is as accomplished as many productions you might see in the West End. Geraldine James plays the actress and matriarch. The doctor is played by Roger Lloyd Peck, recently seconded from the Dibley parish council. Chekhov billed the play as a comedy but nobody in Stoke Newington was laughing.

The Watts Gallery opened at Compton on the North Downs outside Guildford on June 18th. It is said to be the only major gallery in the country devoted to a single artist. Watts was immensely popular in his heyday; two rooms were devoted to his paintings in the newly opened Tate Gallery at Millbank but the fashion for Victorian art changed and by the nineteen fifties you could pick up his paintings for less than a hundred pounds. His museum at Compton fell into disrepair but was rescued by coming second in the BBC’s Restoration programme and then getting a 4 million pound lottery grant. Watts’ paintings are not exactly cheerful. The most famous are allegories of themes like hope, poverty and despair. They are sombre and intense; Watts saw his mission to produce work that encourage young people to think about moral issues.

Lynne Truss didn’t treat Watts kindly. In her novel, Tennyson’s Gift, which described with humour the characters that circled the bard of Farringford, she portrayed him as self obsessed and sexually repressed. Who knows, if he had been more responsive to Ellen’s allures, she may never have felt the need to escape to the stage.