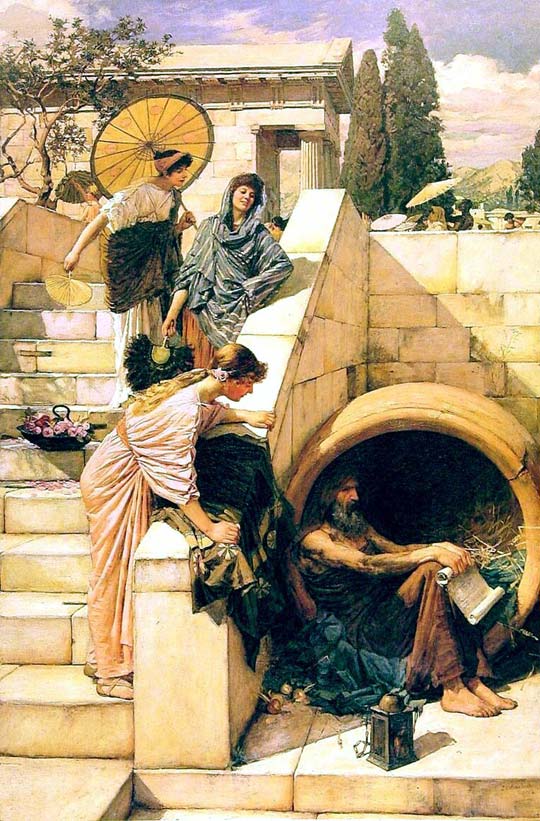

Diogenes in the Age of Reflection

‘You’re rather like Diogenes in his barrel’, David declared on his fourth visit to my little cottage in Edensor. Was that a compliment? Well, on the principle of the glass being half full, I decided that it was. I quite liked the idea of being perceived by the medical fraternity as a hermit, living the thoughtful life, so unworldly that I would ask the Dowager (the nearest we have here to Alexander the Great,) to get out of the sun. Though I did wonder if I have rather corrupted the ascetic image by becoming a bit too busy with politics and The Gut Trust.

We spent the first hour grumbling about how our regulated society was stifling research, inhibiting education, undermining government, taking away the art and enjoyment of life, but risk aversion was part of a cycle. In medicine, it was probably triggered by the dreadful revelations about Dr Harold Shipman; in economics, by the greed of the bankers.

A nervous society finds its ways of getting rid of those who will not conform to its stringent regulations. We are both reading The Hemlock Cup by Bettany Hughes. It’s about Socrates’ life, but takes as its starting point, his death. Accused of being a free thinker and corrupting the youth by speaking against the Gods, Socrates was condemned to take his own death by drinking a cup of hemlock. My old friend, Maurice, was incarcerated in a mental institution last year on the grounds that he was a danger to society. Always resentful of authority, Maurice was targeted by the police and neutralised. Even the spurious interpretation of a brain scan using nuclear magnetic resonance was used to reinforce the case against him.

David and I have reached an appropriate stage of seniority when we can with impunity comment on what we see as the failings of the medical establishment. But this privilege has been hard won. We are both first born and have both shouldered the burden of our parents’ ambitions for most of our lives. David commented that it was not until the age of fifty that he escaped the straitjacket imposed by a reputation in medical research and felt free to indulge his interest in philosophy. At around the same time, he became aware of his parents not just as projections of himself, mum and dad, but more objectively in the context of their own lives. My trajectory ran parallel to his. At 49, I started to retrain as a psychoanalytical psychotherapist and at 53 I retired and began writing my book. Perhaps this was our age of reflection, the time that we could at last be ourselves, rail about the restrictions bequeathed to us by our parents indulge in a more liberal intellectual life.

Does late middle age constitute a similar age of reflection for others besides the eldest sons of ambitious parents?