The Depressive Dance of Denial

It is August 1939, the world is going to change forever but the bright young things still cling to the escapism of the previous decade. Alcoholic hedonism helped this generation blot out the traumas of the First World War, and now they use it to blank out the looming prospect of the Second. Rattigan’s ‘After the Dance’ evokes the emptiness of a lost generation.

David and Joan married in the twenties, a frivolous, romantic excursion from the horrors of the Great War. They were rich, well connected, they could afford not to take life too seriously. So they partied, they drank, they made love; their whole purpose was to have fun. For fear of being thought too intense and to avoid the depression that could bring, they masked their true devotion in a relationship of mutual, just-good-pals flippancy. But there is a serious side to David that Joan failed to nurture; he is a writer, a would-be historian, a romantic, he plays Chopin badly and he is depressed. He anaesthetises the sense of his own pointlessness in alcohol, poisoning himself with self disgust and slowly dying of cirrhosis. And now, as the Nazis march into Poland, he dictates his tedious dissertation on a previous German dictator of much less significance and drinks more whisky.

Redemption materialises in the sylph-like Helen, a trim zealot who has fallen in love with the idea of saving him and is quite prepared to destroy his marriage in order to achieve her mission. When David falls in love with her, you can smell disaster.

Joan, David’s wife, learns on the evening of her party that he is going to leave her. Just for old time’s sake, she makes David play ‘Avalon’ one last time, slips through the curtains on to the balcony and kills herself. A week later, Britain declares war on Germany.

Rattigan sees the glimmering meaninglessness of these not so bright nor young things. He feels their sadness, understands the need to evade reality, but is critical of their somnambulistic trudge to catastrophe. As the one dour party guest, a refugee from the Mayfair set and one-time fiancée of Joan, points out, ‘They ran away from reality after the last war. The awful thing is that they’re still running away’.

The cast are superb. Benedict Cumberbatch conveys not just the surface smoothness of the self-destructive David but also the intelligence of a man who realises he is a wastrel. Naomi Carroll as Joan is stoically jaunty. She carries on with courage, but you can see she is not waving but drowning. Carroll captures the subtle poignancy of their doomed relationship; she knows she got it wrong. Faye Castelow as the trimly seductive Helen, conveys a combination of naivety and determination and a hint of acid that makes her the angel of their destruction.

John, (Adrian Scarborough) is the most likeable character. He is like Shakespeare’s fool, a bibulous court-jester who creates an art form out of his subtle self deprecation, but he also has the wisdom and empathy to warn of the disaster that is about to come.

Everything about Thea Shurrock’s production works, from the orgiastic glee of the ageing socialites, the ghastly over-the-top Moya and her wooden toy-boy, even the glimpse of oral sex on the balcony, and especially the use of a haunting 1920s foxtrot, Avalon, which seems to express the sadness of make believe.

Rattigan’s play opened in August 1939. It was a sell out, but when the reality of the war started to come home to people, the audiences dropped off, the play closed and was not rediscovered until 60 years later.

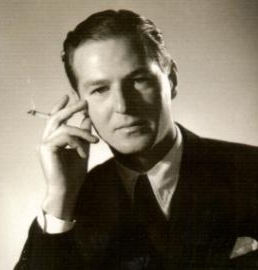

Rattigan’s early life was unhappy. His parents were diplomats but his father lost his position after an argument with the foreign secretary, Lord Curzon. Terence was sent to live with his grandmother who was cruel and controlling. He was very unhappy, but then discovered the theatre and also that he was homosexual, which was of course criminal at that time. Many wondered a gay man could have such deep understanding of women. I’m inclined to say ‘how could he not?’. Surely that is part of the essence of homosexuality; many gays form a much closer identification with women than men; so much so that some are caricatures of women in a man’s body. It is Rattigan’s men who are stiff, like cardboard cut outs in their parted hair, their sculpted moustaches, sports jackets and flannels. This is the emotional repression in the English psyche that often turns heterosexuality into a love that dare not speak its name.